August 11, 2020

133: Astrology Hot Take — What's In The ADA?

Listen

Read

Jessica: Welcome to Ghost of a Podcast. I’m your host, Jessica Lanyadoo. I’m an astrologer, psychic medium and animal communicator, and I’m going to give you your weekly horoscope and no bullshit, mystical advice for living your very best life.

I’m really excited to have you on Ghost of a Podcast. Do you want to start off by just introducing yourself?

Vilissa Thompson: My name is Vilissa Thompson. I am a Black disabled woman, a badass millennial, a proud Southerner, and I am the founder/CEO—CEO of Ramp Your Voice! Which is a blog organization that talks about disability from an intersexual lens, particularly the experience of a Black disabled women and femme needs. I’m a social worker by trade, but I’m a speaker, consultant, writer, and I just love what I do. And I’m also a budding astrology head, so I’m really glad to be here today to talk with you about all things astrology and be geeky in the process.

Jessica: I am so excited you’re here. And I’m so excited to geek out on these two topics, which I feel like is just such a rich point of enquiry—talking about disability rights and talking about the ADA and the astrology of it. So this is really, really exciting.

Also, can I just add that you have a great Patreon page that everyone should research and support and become a part of because you share hella great stuff.

Vilissa Thompson: Yes. You’ll find it at Patreon.com/rampyourvoice, where I do a bit more personal commentary about disability from the intersexual lens—also do a mini podcast on there called Sipping Tea with V.

Jessica: Excellent. And links to all this stuff is going to be in the show notes.

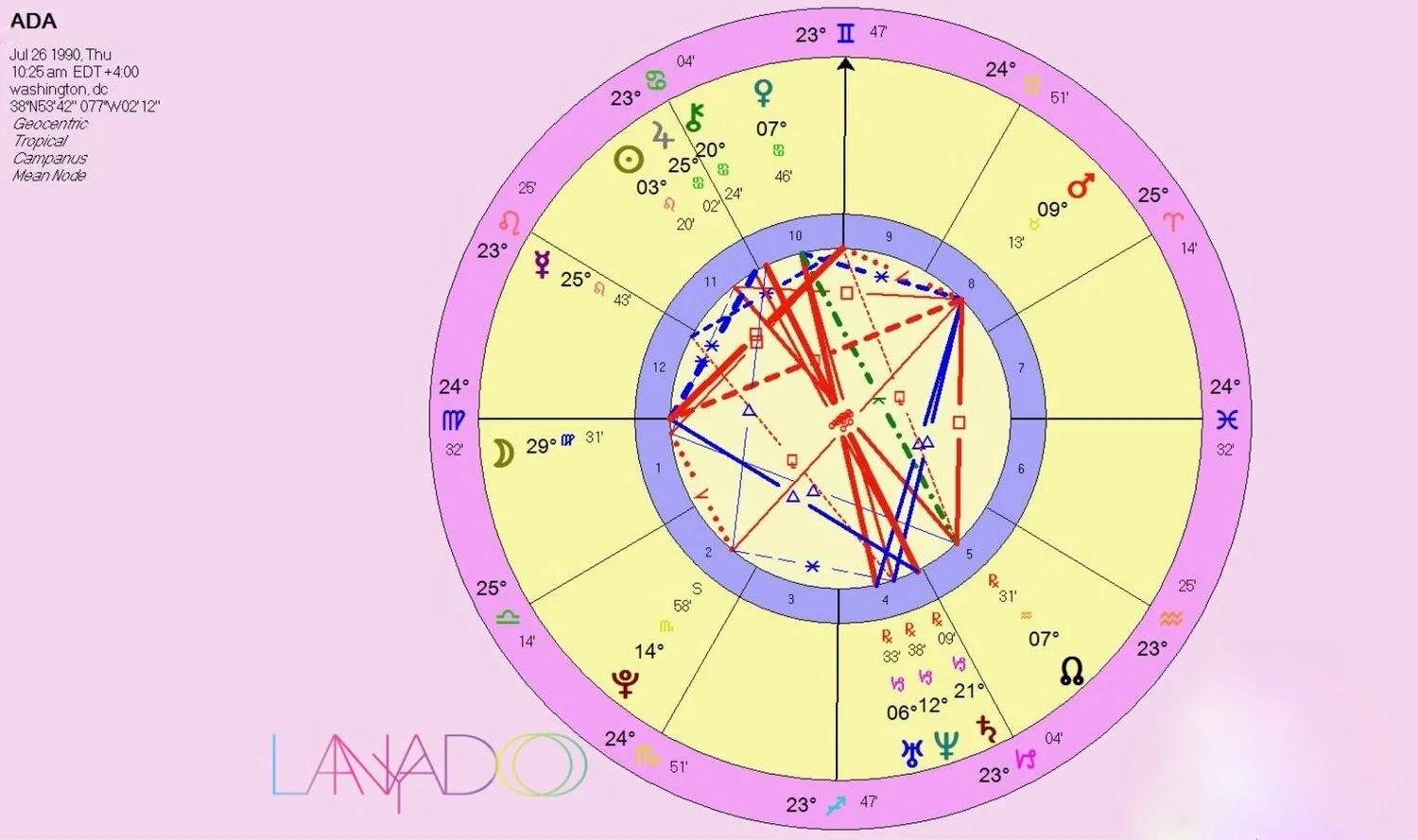

So what we’re going to talk about today is the astrology chart of the ADA, which is the Americans with Disabilities Act. Which occurred—it was signed into law on July 26th, 1990—so recently—at 10:25 am in Washington, D.C. So, if anyone is wanting to pull up the chart, those are the stats of it. And the way that I got that time, in case anyone is curious, was we found the transcript from the law signing event with George Bush Senior, and so the time was on that. So that’s how we got the 10:25 am for this event.

So, are you down to share a summary of what the ADA is?

Vilissa Thompson: Yes. As a member of what we call the ADA generation, for me, the ADA provided protections and rights for us to basically have better access and be included in society. For me, the ADA was very pivotal in my educational experience. I started kindergarten in ’91, a year after the mandate was reassured that I had what is called is a free and appropriate education—meaning that I cannot be discriminated against or receive subpar education, resources, and supports than my non-disabled peers. It ensured that I had protections as a disabled student and that just really become pivotal for me.

My grandmother always states that children like me, disabled children—particularly those in rural South Carolina, in which she was born—did not go to school, did not participate in school. So this mandate along with several others along the way has really enforced the fact that disabled people, especially children, have a right to attend government education and attend schools and to ensure that they have what they need to succeed, not just academically, but also socially as well.

But also the ADA allows disabled people to gain access to public buildings, public entities to where we can go to restaurants, movies, etc. to where they have wheelchair ramps, other accommodation needs that folks may require so that they can be fully integrated into their community and not feel like they cannot engage with society in ways because of their disabilities and cannot be discriminated against because of that as well.

But that’s just a small summary of what some of the protections and the rights that disabled people have been afforded with the passing of the ADA for the past 30 years and how it impacts those of us who are millennials and Gen Z—especially for those of us whose whole entire life knows nothing else but the ADA.

Jessica: And something that was really interesting to me as I was researching—because I had all these assumptions about the ADA, but when I actually started to dig, I was like, okay, so the definition of disabilities is actually really wide.

Vilissa Thompson: I think the—it was just very intentional of the history that I know so that it can be inclusive. You have to think about the time period. We have at that time, the AIDS crisis—we’re 10 years out of that at the signing of it. So we have all of these different disabilities, prime illnesses and so on and so forth, and we want to ensure that it encompassed a big umbrella. That was a quite bit of a fight to do that. It wasn’t easy because there were, particularly for certain conditions like HIV/AIDS where there was push back to include that. So ensured that no matter what disability you have, you have protection from the law.

And there were people who were very particular about ensuring that when this law passed, everyone that qualified did. Inclusiveness, as you found, that it is broad and that was intentional in doing that. But, also, with a fight too allowed that to happen, particularly for that time period. I think when you study these things, we have to remember not just the after effect but also the time period and what were the issues and conflicts and social dynamics of that period.

Jessica: Absolutely, yeah. I mean, even in 1990, the kind of conversation that we were having nationally around mental health—it was just a much smaller, much more conservative conversation. Now, the younger generations—I mean, all teenagers know what mental illness is, and so many kids have diagnosis—for better or for worse—regardless of whatever you think of that. It’s just a completely different world around the conversation around mental health, which is encompassed within the ADA.

Vilissa Thompson: Right.

Jessica: I’m understanding that correctly? Eh?

Vilissa Thompson: Yes.

Jessica: And it’s really interesting as you say that and you bring in the context of HIV and AIDS as being just huge in 1990 when this law was signed, but, of course, the bill was brought to congress a couple of years before that, eh? I think it was ’87 or something like that.

And, so, when we look at this it’s interesting because the North Node of the ADA chart, which is the soul of the chart, is in the fifth house in Aquarius. So we have kind of a sexuality, like individuation around sexuality, and also kind of morals and values around kind of sexual agency in this chart, which I—when I was studying the chart, something that I was really interested in was how historically sterilization had been a really kind of common practice and encouraged practice for people living with disabilities, and this legislation, this law didn’t actually end that, I don’t believe, did it?

Vilissa Thompson: No. It did not. But I’m really glad that you brought that up—it’s that disabled people still being sterilized and institutionalized and then in these institutions were being sterilized without their consent, without their acknowledgment. So we just have that kind of conservative understanding at that time period, even in some regards today, of the right of a disabled person to reproduce, to engage in their sexuality and to engage with sex. So I think that’s really poignant that that is noted in the chart about that type of sexual agency that has not always been afforded to disabled people.

Jessica: It’s interesting too because the chart—and we can talk about this piece a bit more—but the chart, it doesn’t suggest to me that the law and sterilization, but, instead, it’s like the soul of the law—it shifts the kind of social exceptedness of saying disabled people can’t have sex for pleasure, disabled people can’t have sexual agency, disabled people can’t procreate or parent.

And it’s interesting that it’s not in the law itself, and it actually is something that if only astrologers were at the helm of law making, I would say, in 2021, Uranus—it’s already kind of started, but Uranus is going to be squaring the North Node and also conjoining Mars in the eighth house of this chart. And because of these two things there’s actually the potential that over the course of 2021 into 2022 there’s a great potential for amendments to this law that will explicitly advocate for body autonomy and sexual agency within the ADA and making it a more explicit civil rights issue.

What this chart is indicating and what the transits to this chart is indicating more specifically is that there will be more eyes on this topic, and we’re already seeing that and that the more of the populous that is aware of the really oppressive practices of the government against people with disabilities often times, the more social outcry there is. And when there’s greater social outcry, there’s pressure on politicians to make shit change. And I wonder if you know if there’s any kind of push for that within the disability community or within organizers’ or activists’ work right now?

Vilissa Thompson: I think the one thing we were [indiscernible 00:10:03] with the ADA is that what it would give us [indiscernible 00:10:05] to say protections is that it might not have the teeth to always be enforced. And it can’t always be under attack. And with this particular administration and these times, we have seen the intention of chipping away at the ADA or the misuse of the ADA. So I think that is something that we all need to be aware of.

You think of it, “Oh, disabled people, they have rights.” But we may have rights, but it depends on who’s in office, as they may not respect that the fact that we do have rights and to ensure that those rights are protected and enforced and not reduced and weakened. So I think that’s something that we really, as activists, are always discussing with the ADA. And also understanding that even outside of the administration, that the everyday person or organization don’t respect the rights of the ADA either. So it’s always under attack anyway.

Jessica: Let me just back this up with the astrology in this chart a little bit because there’s this stellium in Capricorn. We have Uranus, Neptune and Saturn all in the fourth house of this chart. It indicates a couple of things, and one of them is that so many people living with disabilities are at home or don’t have access to transit. They don’t have access to public spaces as you were talking about. And, so, there’s this way that it’s kind of like out of sight, out of mind. Which is a big part of why I think there’s a way that kind of like even well-meaning activists across the spectrum of issues that people are working on forget, because it’s not in their face, to include disability rights and disability access in their organizing.

There’s another part of it which is this chart holds a Jupiter, Saturn opposition. And, in event charts, when you see a Jupiter, Saturn opposition or you see a Jupiter, Saturn square, what it tell us is that there’s not enough money; that the budget is theoretical and that the indication here is exactly what you’re saying about it not having teeth. It’s ideas—great ideas, but where’s the money coming from?

And it’s easy for governments, not just this current administration—which is clearly not an ally—but it is easy to be like, well, we’ll just take a little bit of money from here, and, well, we don’t have any money to add there. And it is reiterated in this chart with a Mars, Pluto opposition in the eighth and second houses—the houses where we tend to see our money. This is, again, like a constant struggle. So, it looks like from this chart, money gets earmarked for the ADA, and then it gets taken away. So it’s like this kind of constant reshuffling, and it’s what you’re saying, again; it doesn’t have teeth. It’s like it looks and sounds better than it actually is when push comes to shove. And it looks like that is kind of like across the board when it comes to implementing the ADA.

Vilissa Thompson: Yes. A good example of that is the transportation piece. They’re still—transportation systems are not accessible. A great example of that is the New York City subway system. There’s been countless actions taking place—legal actions taking place against the transit system there to upgrade to ADA and I think there’s only probably a few subway systems that are fully accessible out of, I think, 100. I know that the subway system there is pretty robust. So, it is really astounding at how 30 years later, a very big system like New York Transit and the subway system isn’t up to code. And you would think a city who has the resources to do this and has the time to do this has not.

So this is where we see some of the gaps with the enforcement of the ADA and governments and agencies who utilize government resources and supports and not using those supports and services to upgrade it, and, also, will fight against the call to upgrade and be having to be sued to bring this forward.

So, yes, I think there’s a lot of kind of give and take of funding not being pushed towards giving disabled students the resources and supports that they need or upgrading the public transit system. We see the money always be allocated elsewhere instead of where it needs to be so that disabled people and everybody can utilize it. Because upgrading a subway system doesn’t just benefit disabled people; it benefits parents with strollers. I know there was the incident a couple of years ago where the mum had an accident and then she passed away from falling with her child and the stroller. So access that benefits everybody. It’s not just this particular community.

Jessica: Yes.

Vilissa Thompson: That’s a great point to make about that teeth and the limitations and where the funding goes and doesn’t go. That really is dire for not just inclusion, but just ensuring that everybody can engage with the world safely and fully.

Jessica: Yeah. And it’s such a fucking shame that people feel—have to feel like it directly benefits them to get on board for this, so I hope people listening to this are like, “That is jacked. I’m going to start caring about this and mobilizing about this and making noise about this.”

But I really do think that anyone who uses public transit, which in metropolitan areas is essential to have access to public transit. Everyone eventually is going to need elevator access to the subway. People, you injure your ankle—you don’t have to have it as a long term issue, and you’re going to be really grateful for having an elevator that can take you into the subway as opposed to a million stairs, which are completely inaccessible.

It’s interesting because Mars in astrology—it’s like fast transportation on land. So it’s like the subway. It’s the bus. And having Mars opposite Pluto in this chart—it’s also squared by the sun—it, unfortunately, clearly indicates the complete failure of the ADA to create—I guess the best way I’m thinking of saying it is like iron clad law around the need for transportation being accessible. And there’s a lot of forms of transportation that exist, but it’s not always accessible in terms of it being physically easy to access but also financially accessible. There are services that are just really expensive, and they don’t even work.

I’m lucky enough—I’m in the Bay Area, and when I worked with developmentally disabled folks for many years, and I worked with lots of people who had mobility issues or were in chairs, here in the Bay Area, we’ve got a very accessible public transportation system, and even within that it was often broken, and there was lots of problems, and the kind of hygiene standards were not the same as on the trains and in the station in general. It’s a damn mess, and it's something that we should all be concerned about, even if we are not as individuals directly impacted. It’s a civil rights issue. And it’s a deeply important one because how’s you going to get to work and school, let alone to social events and job interviews and all that kind of shit—getting to medical appointments. You need public transit.

So the other thing is this back to this like Saturn, Neptune, and Uranus conjunction. Most of those planets are conjunct—Saturn is a little wide—in the fourth house. The ADA, what it does do pretty effectively, as signified by all this Capricorn shit, is building codes. It does look like that’s one of the more effective places where the ADA has actually been able to do what it was supposed to do. Has that—is that also line up with what you have seen, that building codes are something that the ADA is pretty successful with?

Vilissa Thompson: Yes. But I know that even when some of that is about the buildings who are older being either [indiscernible 00:18:00] and the stipulations surrounding that. And, also, where older buildings, I know, on a modern point, they’re, of course, had to be ADA compliant. And sometime their ramps are in the back of the building, so you have to—instead of going to the front of the building, you have to go to the back. Or you can have a very long ramp, which may or may not be very safe, but it’s the way they have to be structured to meet the way that the building was already there.

So newer constructions, of course, have to be ADA compliant. But the older constructions—it depends on where you are, particularly, if you live in a more rural area. You know, those may or may not be up to code, so that is something where the architectural aspect of the law can be a little shaky. And that depends on resources and supports, whether was that allocated—it all kind of goes back to money.

The importance of putting money to ensure that everybody has access. And, honestly, everybody, again, benefits from having elevators or maybe having an entryway that doesn’t have steps or have an entryway that is in the front and not in the back to where you may have to go to the kind of shaky parking lot that maybe gravel or maybe dirt. So I think that’s a very big thing to where it does impact in the building codes. But, again, it depends on how new or old that building is and the priority that has been given to ensure that the code standard is up to date.

Jessica: So, as you’re saying that, I’m like, oh, right, there’s Venus at the top of this chart, which actually indicates everyone felt really good about themselves when they were signing the ADA into law. They were like, “Look at what wonderful people we are. We are grand.” It was just like a feel-good law. But then Venus is opposed by Uranus and Neptune. So it’s like this kind of structural almost erosion to what the intention behind the ADA is.

Again, if you don’t have money, how are you going to be compliant to these laws? How can you invest in these laws? And, if people who have to use these back-door entrances are out of view of public, then it kind of perpetuates the reality where people aren’t thinking about it because it’s not in front of them.

One of the things that is actually really positive that is happening right now is Pluto is forming a trine to the Ascendant. So the identity—so the sun and the Ascendants are both identity points, so this is kind of like the identity of the ADA. That has, I would imagine, brought the conversation of disability rights in to the fore. And that’s just happened to have coincided with the 30-year anniversary of the ADA, which is just really great for our intranet who loves to gobble up news and talk about things when they are on trend or whatever. It’s coincided, and so it’s a moment that can be leveraged, which, actually, it does look like it’s really impactful. And it’s a two year period that when it’s over, shortly thereafter, Pluto will form a trine to the moon of the ADA. So there’s actually—we’ve entered into this period where there’s more likely to be more care and attention to the ADA itself. And, of course, that coincides with COVID-19.

Donate to Feeding America’s Coronavirus Response Fund. No one should go hungry during the COVID-19 pandemic. With school closures, job disruptions, and health risks, millions of Americans will turn to food banks for much needed support. They can’t do it alone, so, if you can help, please do. Go to feedingamerica.org.

As you shop for masks in this new normal that we’re all living in, consider others who rely on lip reading and facial expression for communication. Look into getting a clear mask, sometimes called a smile mask. Just look them up and consider buying them when you buy masks for yourself and your family.

The Okra Project is a collective that aims to mitigate food insecurity in the Black Trans community. The project hires Black Trans chefs to come to the homes of Black Trans people or community centers, if they’re currently experiencing homelessness, to cook healthy, culturally relevant, and delicious meals. They feed bellies with great food and feed spirits with great fellowship.

The Okra Project intentionally has never sort 501 (c)(3) status, so they can ensure that their money goes where it’s needed. Therefore, their work is maintained entirely through individual donations from people like you, and everything helps. Learn more about their programming by visiting theokraproject.com or donate, and the link is in my show notes.

Jessica: Have you seen any kind of shift in response to or around COVID-19 with the ADA and disability rights?

Vilissa Thompson: Yes. With the pandemic itself, we’ve been seeing the misuse of the ADA regarding wearing masks and the abuse of it. And that kind of goes back to the weakness of where people abuse the meaning of ADA and can distort it for their own gain. So we see that going on right now.

But, also, wondering about the school year starting—what does that mean for our disabled students? Many of them have had already to adjust to this learning at the end of this past school year, and now with the uncertainty of do they go back in the classroom, do they do all virtual?

Everybody maybe famil-, well some people—hopefully everyone—will be familiar with the story of Grace, who was the Black disabled girl in Michigan who was unfairly punished for her inability to adjust due to her disability through online learning. And she was criminalized with that—she was placed in the juvenile justice system for not finishing her homework. And that is something we need to keep a watch of, and how—

Jessica: —And she’s been released, right?

Vilissa Thompson: Yes. She has been released.

Jessica: But she was incarcerated for a couple of months, wasn’t she?

Vilissa Thompson: Yes. Yes. Yes.

Jessica: Horrifying.

Vilissa Thompson: And, if it wasn’t for the activism of those activists and organizers in that area and also the media coverage, she probably still will still be in that institution. The judge would not allow her to be released when the hearing came, and it was just so heart breaking to have a child who just wanted to go home and to have a child who didn’t do their homework because they had a hard time adjusting.

I think we have to be mindful of children are being traumatized by these times as we are as adults, and they don’t always have the words to say, “I can’t be in this moment.” And, some of them, if they do say it, they’re not going to be respected.

So I think that what we’re going to see is how the ADA will be used to either uplift our disabled students or not. And who gets to be uplifted and protected during these times if they don’t adjust well to this new quote, unquote normal of what we’re dealing with when it comes to schooling and who gets punished or not. I think that my biggest fear is, are our disabled students, particularly those of color, being unfairly punished like Grace was for not getting to the rhythm of everything and not having their disabilities and their particular needs considered? And having a type of empathy and understanding and extending grace and care for our students. So I think we need to be very mindful of who’s going to be harmed within our school system—not just by getting sick, but also by possible criminalization and by being left behind when it comes to their academic success.

Jessica: Yeah. There’s two things that really come up for me around that. One is that I wonder if there’s some sort of kind of resource for students who do have disabilities where they get free tutoring that is of quality, and I wonder if—my brain goes instantly to, I wonder how many people could actually volunteer to be tutors to help students who are struggling. Does something like that exist or an organization like that exist?

Vilissa Thompson: I’m sure probably on the maybe state and local levels of [crosstalk]. But I think that’s a great idea if people want to do that. Maybe folks who used to do tutoring in person or used to do tutoring if they were in high school or college. Maybe that’s a service in which you can offer students who may need a little extra help, who may not be able to adjust, may not be able to get a teacher’s individualized attention. If you’re feeling like, “What can I do?” Maybe that’s something you can offer.

Jessica: Yeah. Yeah.

Vilissa Thompson: And I think that’s something to kind of maybe all of us think outside the box as to how we can support our students as they go back into the classrooms and thinking about what would they be missing if they’re not in the classroom that they would need assistance in. I think that’s a great idea for people to think about.

Jessica: Yeah. So here’s where it brings me to the next—the next thing that comes up for me from what you’re saying. So, in this chart of the ADA, we have Jupiter, the planet that governs education, in the eleventh house. And that’s the house of community, right. And so part of what the ADA successfully did do—I mean, not perfectly, but something that it did do is what you talked about at the onset of our talk, which is it kind of made education more accessible. And it kind of brought students into the classroom and gave them more support.

Now, unfortunately, what we have happening astrologically is the planet Pluto is forming an opposition to Jupiter, which, unfortunately, can make things a lot worse within the education system—in walks COVID-19. And teachers who were burnt out before, now, all of a sudden, they have to learn how to teach online or they go to school, and it’s like a whole new set of risks for them and that just burns them out and makes them have less internal resources to share with students who need more attention.

So we have the kind of risk of, unfortunately, resources becoming a lot more scarce. The positive of a Pluto opposition to Jupiter in this chart is that it can force the conversation, make it more public. It’s kind of like, unfortunately, I hate to use one student’s personal situation as an example, but with Grace, it was so awful what happened to her. It probably wasn’t that new or shocking in the context of the shit that goes on in the world, but because of the world as it is and because of the constant 24 hour news cycle, we have the potential to have more light, more eyes on this problem so that there can be transformation and movement on the topic. So this Pluto opposition to Jupiter has really great potential for things getting worse, but also for things getting better. For there to be more awareness and then a transformation around how we react, how we respond as a society.

And that brings me to my third and final question from all the things you just said. You mentioned how the use of masks is being kind of misappropriated or misused. Can you kind of unpack or explain what you mean by that?

Vilissa Thompson: People are basically saying that just kind of using the ADA as a way of not wanting to wear the mask—saying that they cannot wear the mask; they’re this and that and the third.

Jessica: They’re—so, wait, the people who are saying I can’t wear a mask because I can’t breathe or whatever it is, they’re standing behind the ADA for that?

Vilissa Thompson: Yes, to a degree. So they’re basically misusing the ADA for their own individualized gain. Of course, there are people who cannot legitimately wear masks, that’s—I want to make that plainly clear.

Jessica: Absolutely, yes.

Vilissa Thompson: But these people are individuals who most likely can wear a mask but don’t want to wear a mask. And that is a huge, huge problem because you’re misusing a law for your own selfish reasons. And that’s basically what this is, people being selfish, people—and we’ve seen how this goes over the past few months of people being selfish about not wanting to look out for their own health but also the health of others.

So this misusing of the ADA isn’t—isn’t foreign necessarily when it comes to the ADA, but I think it’s really shocking to see people misuse it in these times to where we know the effectiveness of masks if one is able to wear them.

I know—in the same vein, when it comes to the punishing of students who may not wear masks to understand how that goes as well, particularly in a school environment. So being mindful of how the resistance of not wearing masks can look very different based on the setting and based on the who of that—who can wear masks and who cannot and the reason why and the enforcing of that, particularly when it comes to our schools and how, again, students of color—disabled students—disabled students of color may be unfairly targeted by their inability to wear masks that will most likely be legitimate and be again punished for not doing so or punished for not following the rules.

Jessica: Thank you. Yes. Yes. Yes. And Mercury is in the twelfth house of this chart, and what it does is interesting. It’s almost like it silences teen voices, which is an odd thing to see in the ADA chart. It makes me wonder exactly what that’s about or—I’m not exactly sure how to interpret that.

I almost wonder if the way that the ADA supports disabled students that are not university age students, but high school students, middle school students, if it kind of keeps them separated from each other so that they’re not actually able to organize and all of that. It kind of shows up in the chart that we do see so much activism from teens, but when you’re dealing with everything of being a teenager in addition to dealing with disabilities it is just like another hurdle. Is there any kind of like community component, like a kind of bringing students together in the ADA? I don’t know that there is.

Vilissa Thompson: I think the one thing that I found is that with disabled students there can be segregation based on placement where the students are in corporate mainstream classroom or the special education, corporate special education classrooms. And, again, adults can get in the way of students having this community for themselves.

I know that from my own experience, there was this great divide between us students who were in the mainstream classroom versus students who were in special education and the world’s not merging together. Even though we all knew each other, even though we all fell under the special education umbrella, but there was that separation of us based on placement. So I think that adults kind of stand in the way for disabled students to band together, to talk about the ways in which their schools and communities can be more accessible, how they’re being discriminated against, how they’re being harmed.

And that type of community is needed, particularly in the teenage years as you’re figuring out your bodies, your minds, what you like, peer groups, and peer pressure, and all that. It would be the time to where disabled people who are growing up to their identities on many levels would have that type of community which would allow them to build, to [indiscernible 00:33:55], to have that community, to have people who understand who they are without always having to explain it to everyone else.

So I think that it would be wonderful to see disabled students be uplifted to become activists and activists at that young age and watch them grow into that. I think that is something that we need to allow and to really allow them to flourish and to uplift them in that process. Of course, there are disabled activists who are teenagers, but it would be great to see how much more we would have if there wasn’t those barriers or that segregation in existence.

Jessica: Yeah. I mean, it’s interesting. I actually think that the Pluto opposition to Jupiter and the Uranus transits that I mentioned earlier—Uranus conjunction to Mars in the eighth house and squaring the North Node in the fifth, all indicate that there is a potential that we will see greater organization now, in part, because I think a lot of students are learning online, and so in a way it makes it a lot more accessible for disabled people to find each other and to band together because they’re doing it on a Zoom, instead of having to navigate physical space.

Vilissa Thompson: Right.

Jessica: This very problem of kind of like the lack of socialization that’s encouraged and facilitated within the schools, I can’t help—when I look at this chart of the ADA—to wonder if that has to do in part with the lack of validation and support around the sexual agency of disabled teens—of recognizing that part of why we socialize in high school is ‘cause we need to get our flirt on or we need to be tortured by a crush or whatever; that is part of being a teenager.

And I think this desire to desexualize people with disabilities it’s really problematic because having body autonomy, having pleasure through your body, having feelings, those things are part of the human experience. This idea that sex and sexuality is for procreation, we all agree—or most of us agree—is really outdated, and we reject it. But it still gets projected onto people with disabilities in a way that I think, again, the ADA chart actually articulates that.

It articulates it in several places, and in those exact places of the chart, those are places that are being challenged astrologically in 2020 and 2021. Thank fucking God. Let’s keep talking about that because I think it’s really important that we encourage people to get to know their bodies and get to know their feelings and validate their autonomy, so this is—this is, again, it’s all in the damn chart.

I want to just point out one more tran-, well, two more transits, if I can. Can I steal you for a few more minutes?

Vilissa Thompson: Yes.

Jessica: Okay, cool. So one thing I want to acknowledge is that at the end of 2019, it was the Saturn return, so it was the first time of maturization of the ADA. Do you remember what was going on, if anything meaningful, in December of 2019 in regards to the ADA? This was before COVID-19 become a global sensation.

Vilissa Thompson: Yes. I think I shared with you the administrations fighting with more—have supported more for the institutionalization of disabled people, and we know how that goes with the history of storing us away, kind of that being exclusive but also acting like we don’t exist.

Jessica: Yeah.

Vilissa Thompson: And, as such, they get to [indiscernible 00:37:27] the laws. I know we talked about before and so I think that the kind of, in some ways, winding back the clock, is that we see that this administration particularly does, and it does it with everything else. So it’s pretty on brand, sadly, in this regard.

But it is really kind of winding back of the rights of disabled people and the rightful fear for what that means for those of us who maybe particularly vulnerable to possibly being institutionalized again for whatever reason—the reasoning for anybody’s institutionalization of their disability. So I think that all of these things that we see the administration doing at the chipping away of the ADA, whether it’s a big chip or a small chip, that is still impacting the strength or lack there of in some cases of the ADA to be effective and to be by their standards weakened and not strengthened.

But there’s a lot of work that can be done to strengthen the ADA. But this administration and the support of this administration do not see it as a priority to protect it and to ensure that it’s enforceable for everybody. And, again, that access, that enforceability goes beyond just disabled people.

Jessica: Yeah, absolutely. It’s interesting because when I think about the Saturn return, I’m not just thinking about the event of the Saturn return, although, yes, very fucking much so, but also it’s the opening of a new 29 and a half year cycle of the ADA. And over these next three years, post Saturn return, this is a particularly fertile time to be thinking legislatively and to be thinking culturally and to be having public conversations about the reach, impact, and very structure of the ADA. My great hope is that this happens.

And that brings me to the kind of final thing that I wanted to name, which is that next year in 2021, the ADA’s midheaven is going to go through a square by Neptune for about two years. And, so, my hope is that what we see is a lot more media—TV, movies, anything visual media that is both becoming more accessible but also tells more stories of disabled people and has more disabled people telling their own damn stories and being at the table for the kinds of stories that get told and how they get told.

This is one of the great things about Neptune is it governs media and the power of storytelling. In particular, the reason why I say visual storytelling is because Neptune is at like—it’s like movies and TV’s and shit like that. So it’s that kind of storytelling as opposed to just writing or just audio. And this is something where we—the more we see a cultural shift where people have a personal kind of like stake in it, the more activated we get, the more likely we are to get kind of change in legislation.

So it’s like anyone listening who works in Hollywood, tick, tock, get on it right now. You are late to the party, but, please—welcome—come.

Vilissa Thompson: Yes. And also making sure that when we tell disabled stories it not be white, single, male system of stories because there are disabled people of color. There are disabled people of color who are queer. There are disabled women of color, and there are disabled Black women. So I think that’s something we all need to keep in mind when we think about a lot of disabled media. But visually there’re like movies and shows, it is typically the stories of white, disabled men. And I know I’m tired of it, and there are many of us in the community that are tired of it. So, if you are somebody with power and resources to support in Hollywood and other industries, don’t go to the good old standby of white disabled men storytelling. And also move away from hiring non-disabled actors playing disabled roles as well.

Jessica: Yes.

Vilissa Thompson: Which is what we call tripping up is when non-disabled actors play disabled characters. So understanding that there are disabled actors and actresses, there are disabled writers, producers, directors, and so forth. So, if you don’t know the story, there are plenty of us out there, myself included, who could tell you what kind of stories we will love to see.

And to diversify that storytelling that will allow society to understand the disabled experience outside of the non-disabled gains, outside of the non-disabled understanding of disability that—that feels good, that doesn’t really feel good to disabled people. That’s for non-disabled folk, that kind of sympathy, pity, or like, “Oh, it’s a disabled person; I feel so sad. Oh, it’s a disabled person; can I help?” Those type of storylines don’t do anything for us as a people; they are more so for you all. So paying attention about not only who’s inside the camera and behind the camera, but also the stories being told that is truly reflective of the biggest minority group in this country and the world.

Jessica: Hmm. First of all, beautiful. Yes, thank you. Also, I love on your Twitter bio I think it says hashtag disability too white.

Vilissa Thompson: Yes. Too white.

Jessica: Yeah. I love that hashtag. I don’t know if you came up with it or if you just like—

Vilissa Thompson: —Oh, I did.

Jessica: You did? It’s amazing. There was, wait—there was something that you said the first time we talked about this, and it was so important because I asked you about the word disabled or disability because there’s this evolution of language with all identities. But you said not using the word disability—you said if that’s for me, it’s not for you. You said that being disabled is a huge part of your identity just like racial identity or sexuality or gender identity.

Vilissa Thompson: I think that with disability, people look at it as a pity thing or a sorry thing, and by sorry, I mean, like, “Oh, my gosh. I’m so sorry that happened to you.” And it’s like, nothing happened to me; this is who I am. And instead of seeing disability as a sense of empowerment, as an identity, as a sense of pride, as a community, as a history; disability is very rich. We are a very rich people with a culture and complexities that just really are not understood. Not because it’s hard to understand, but because there’s not an effort to understand—not an effort to understand us and to see us as people. People see us as our diagnosis and not as whole.

As a social worker I have this holistic understanding in my approach and how I deal with people in my practice and how I view the world. And disability—disabled people especially are not afforded that. And when you have other marginalized identities like color, being queer, Trans, and so forth, your humanity definitely gets disregarded on top of your disability.

So, for me, when I say that I’m disabled, it’s re-claiming an identity that was stripped from me because of societies ableism. Because of society’s ignorance about what it means to be in these disabled bodies or minds or what it means to possess them, and the ignorance surrounding that that society doesn’t choose to correct but instead projects onto us.

So I think that disabled people are disabled, not because of who we are, but by society’s understanding of who we are—by the discrimination, the prejudices, and the biases that impact our quality of life, impacts the opportunities and supports for us to thrive and not just barely survive.

Embracing and reclaiming the terms disability or disabled is an act of empowerment, and, in some ways, an act of defiance and to what society deems us in these—in this particular life experience, and who we are versus what they deem us to be that does not at all align with our essence.

Jessica: Hmm. So beautiful. I just—I cannot thank you enough for spending this time with me and helping me unpack this chart. It’s Patreon.com/rampyourvoice, right?

Vilissa Thompson: Yes.

Jessica: People, you really need to go to rampyourvoice.com where there’s just so much.

Vilissa Thompson: Yes. Yes. And you can also hire me as a consultant or a writer or public speaker. I’m doing a freelancing life right now, so…

Jessica: Great.

Vilissa Thompson: So, yeah. I am available for your organizations in case you want to add a disability justice lens or an intersexual lens. I’ve been doing some work with the movement spaces, particularly Black movement spaces, about giving them, in some ways, information [indiscernible 00:46:47] when it comes to understanding how disability justice is an instrumental part of movement work, and how to be intentional about including Black disabled folks and what they do. So I am available for hire.

Also just be supportive of the work of Black women and particularly Black disabled women since we are not as visible as other women groups. So just be intentional about if you follow folks on Twitter or Facebook or whatever, who are you following and are they giving you their work, in some ways for free? If you’re following us on Twitter, are you learning? And if you are, throw a little money into the collection pot if they have a Patreon like I do—support or hire them for certain services that they offer. So now is the time to really uplift disabled people and particularly those of us who are of color, and, in my case, Black disabled women, in what we do.

We’ve given ourselves so much, deathlessly in many cases, to this work, and it is great to be supported by your listeners and anyone else who stumbles upon what I do, and just really feel loved. This is a lot of work. It’s not easy being in this predicament of being outspoken and having to speak against injustices, but it’s a calling that few answer, and it’s one that I answered. And I always find eventful ways to frame my work into new stratospheres, just like being on your podcast, Jessica. I’m a novice in the astrology realm and learning, so it is just really great for us to connect to bringing two passions together effortlessly.

Jessica: I just—I love your work. I love what you do. I am so grateful that you’ve spent time on the podcast and am just really hopeful that more people go forth and support you on Patroen and also hire you for your consultancy work. All links will be in show notes.

So I guess we did what we came here to do.

Vilissa Thompson: And know we had a good time doing it too.

Jessica: And we did. And we did. Thank you so much. Thank you so much.